In 1876 a British Explorer smuggled out seeds of the rubber plant from deep within the Amazon Forest and ferried them across the Atlantic to the British Isles, from where they spread throughout the empire.

Today India is one of the top 10 countries producing natural rubber, but the rubber now being produced in mainly the southern and eastern states of the country isn’t completely native to the land but was brought from the other side of the world.

Back to 1839 a very important invention was made by the chemist Charles Goodyear. Working for a rubber Company in Woburn, Massachusetts, Charles discovered that combining rubber and sulphur over a hot stove caused the rubber to become rigid, it was called vulcanization.

Why is this important? because then the thought of turning the latex, the liquid fluid coming out of a rubber plant into durable and stretchable materials suddenly became possible, there was however one problem, most of these plants came out from one place.

The hevea brasiliensis or the para rubber tree was native to Brazil and was particularly found near a city called Manaus some 1500 km up the Amazon. The rubber boom came, people flocked to the Amazons, and Manaus in a short while became the rubber hub of the world.

The rubber boom surprisingly didn’t prove profitable for the natives, many historians claim that Brazil’s rubber trade in the mid-19th century spawned a criminal organisation like no other, flouting rules, bonded labour, and everything corrupt was included in the process.

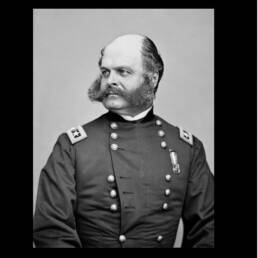

And if there was a way to make a fortune in any part of the world, how could the greedy bunch on the British Isles be left behind? Enter Henry Wickham, a native of Hampstead, North London. Wickham landed in Brazil around 1873 and saw for himself a God sent opportunity.

Wickham, then in his late 20’s, realised that vulcanised rubber was slowly revolutionising the world. Electric insulation, bicycle tires, and future war machines all needed the material at some stage and Wickham instantly recognized this chance to make a name for himself.

Wickham came up with a back story about his research in new species of plants and started going to the rubber groves deep in the amazon near Manaus, where he was able to carefully collect the rubber seeds.

Historians claim that it might have been odd for Wickham to just sneak in and take those seeds without the locals knowing about it, but once he declared that the seeds were of the academic specimen, a term Brazilians often associate with not viable seeds, Wickham easily got away.

After collecting a wholesome amount, he loaded the seeds on the SS Amazona and sent them to London’s Kew Gardens, and within a few weeks some of the smuggled seeds were sent out to various parts of the empire, but mainly in southeast Asia.

Wickham himself accompanied the seeds to London where he saw them being dispatched to British Ceylon, the Malaya peninsula, and Africa. From Ceylon, some of the samples then made their way to the South of India, where cultivation started in the late 19th century.

Wickham’s thievery not only helped to dismantle the monopoly of countries Like Brazil and Peru but also jumpstarted a whole new market for rubber, under strict supervision plantations in the southeast of Asia became commercially viable and more productive.

Wickham claimed to have smuggled out almost 70,000 seeds out of Brazil though that number has been heavily debated. Wickham was knighted on 3rd June 1920 by King George V for services in connection with the rubber plantation industry in the Far East.

The story of the Brazilian rubber doesn’t end here. In the 1920s the British still had a stranglehold over the rubber trade and this was becoming an issue for American automaker, Ford. What happened later is quite interesting.

Eagerly looking for alternative supplies of raw materials needed for the Ford Model T, Henry Ford bought a concession of 3,900 sq miles of land on the banks of river Tapajós near the city of Santaré in Brazil, hoping to cash in on the local production of rubber.

Work on the town was completed in 1928 and it was named Fordlândia. Strict working hours, bad American food, and the ban on playing football within the premises irked the local workers however who went on to revolt.

In 1934 after only 6 years and numerous problems Fordlândia was abandoned by the Ford Motor Company. The project was relocated south of the city of Santarém but with the coming of synthetic rubber in 1945 that project also was abandoned. Fordlândia is now a Ghost town.

If you visit Manaus today be sure the check out the Amazon Theatre, believed to have been built with rubber money. Having witnessed a history of human violence and corruption it stands today as a magnificent edifice waiting to recount its story to eager listeners.

Sources: The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power and the Seeds of Empire by Joe Jackson; What Brazil’s 19th-century rubber crash could teach today’s oil drillers, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2022/12/20/what-brazils-19th-century-rubber-crash-could-teach-todays-oil-drillers;

Image Attributes: Sir Henry Wickham, from @WikiCommons; A photo of enslaved Amazon Indians from the 1912 book “The Putumayo, the Devil’s Paradise”, from @WikiCommons;

Commercial center of Manaus in 1904, from @WikiCommons; Processing of rubber, Manaus, 1906, from @WikiCommons; Portrait of Henry Ford, from @WikiCommons, 1925 Ford Model T touring, from @WikiCommons; The Fordlândia water tower, from @WikiCommons; Ariel view Fordlândia, by Jeso Carneiro / FLICKR; Amazon Theatre, from @WikiCommons