A cloth from India so evocative and luxuriant that it had people around the world drooling over it and governments in raptures trying everything in their power to ban it. The story of Chintz.

Around the late 18th century, a celebrated actor and theatre manager in London David Garrick commissioned Thomas Chippendale, a cabinet maker famous for his neoclassical designs to make a bed for his villa at Hampton on the Thames riverside.

The hangings for the bed were supposed to be original Indian Chintz and were presented to Mrs. Gerrick by a friend from Calcutta. To the couple’s amusement, the bed hangings were seized by British customs since there was a ban on the import of Indian Cotton.

Mr. and Mrs. Gerrick had to later plead to get the bed hangings released, but such was the craze for Chintz back then that governments all around Europe were putting restrictions on it.

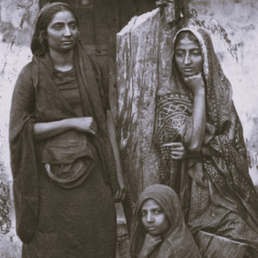

Originating from the Hindi word chint meaning meaning “‘spotted’, ‘variegated’, ‘speckled’, or ‘sprayed’, the fabric is supposed to have originated in the sub-continent thousands of years ago. The fabric is particularly famous for its dyed decorations, especially the floral motifs.

Back in the 15th century when Vasco Da Gama returned to Portugal after finding the sea route to India, he not only bought back precious spices but also a handful of precious Indian cotton. It would, later on, give rise to high demand for the fabric resulting in the Calico Craze.

Chintz was initially used for home furnishings to beautify small antechambers and bedrooms with colorful carpets, wallcoverings, and bedcovers. The images featured in the Chintz were typically the Iranian and Chinese-inspired ‘flowering tree’.

The Indian Chintz had a particular glaze to it and in the later years of the 17th century, the fabric was used to make clothing. Indian artisans were given specific instructions to make them with European aesthetics. The Business quite literally boomed.

In France, it was first sought after by the aristocracy; as in England and Spain but it was not long before the working-class women also adopted the fashion, in other words wearing Chintz became the trend.

While importers of the Chintz gained massively from the movement, many merchants who still dealt in silk and wool almost rioted against the foreign fabric, ultimately leading to many governments banning the fabric.

In France the fabric was fully banned between the years 1686 and 1759, in England, there was a partial ban on imports between 1700 and 1774. There were similar restrictions in Spain, Italy, and even Turkey.

Even after getting banned, the demand didn’t wane, the traders started smuggling the fabric into many countries. It also fuelled local industries to copy the Indian Chintz. Chintz made in England in became widely popular.

The ones made in France came to be known as ‘Les Indiennes’ and were also very popular as table linen and also as the fashion fabric. The effect of the India chintz was replicated to almost perfection be it the flowering trees or the exotic bloom.

Some of the effects of the fabric were not so humane however, the surge in demand led to the surge in the slave trade in the Americas. British and European planters started bringing in slaves from West Africa to man the cotton fields and meet the demand.

Chintz fell out of fashion in the mid-19th century, though it tried several comebacks. British songwriter and pioneer of the glam rock movement Marc Bolan sang about the fabric in his song ‘upon the seas of Abyssinia’.

In the 1980s, it was used extensively and popularised by interior decorators like Mario Buatta who was called ‘The Prince of Chintz’. In 1996 the Swedish furniture brand IKEA came out with its influential ‘Chuck Out Your Chintz’ ad to promote their own brand.

Interestingly it may have been British novelist George Eliot who popularized the term, in a letter penned to her sister in 1851 giving her opinions on some fabrics “The quality of the spotted one is best,” she said, “but the effect is chintzy”.

Sources: