The blasphemous literature that shook Hindustan

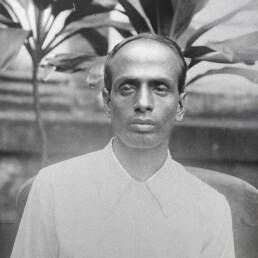

In 1908, a collection of short stories titled Soz-e-Watan (The Dirge of the Nation), was published by an author named Nawab Rai. It was a time when literature was becoming a bit too seditious for Westminster’s liking. Soz-e-Watan was precise, hard-hitting, and defiant right down to its every letter. The British government wanted it banned; the problem for them, however, was that they couldn’t find any author named Nawab Rai. It was a pseudonym. When they did manage to track down the actual author, it turned out to be a government employee by the name of Dhanpat Rai Shrivastava. He was subsequently banned from publishing any kind of literature without the prior permission of the authorities.

More than defiance, when Soz-e-Watan got published, it was the first time the Urdu literary scene got a taste of the short-story genre.

Fast forward to February 1933. While in most parts of the country the Civil Disobedience movement was raging on, in Lucknow, there was chaos in the small office of the Nizami press. Victoria Street near the chowk was swarming with police — a raid was underway. A raid for publishing blasphemous literature.

The press owner, seeing the mayhem outside, agreed to give away all the unsold copies of the supposedly profane book to the authorities. But if history has taught us something, it is that banning a piece of literature has rarely ever served the desired objective of restricting counter views and opinions

The book, which was ironically called Angaare, loosely translating to ‘Burning Embers’, spread like wildfire. As if it was in its nature to scorch age-old orthodoxy and patriarchy in its wake while paving way for a literary movement unlike any of its kind before.

Angaare was an outpouring of emotions much like Soz-e-Watan that preceded it. Those unbridled emotions had slowly built over time, waiting for the opportune moment to erupt. In the years following the great war, buoyed by a nationalist fervour, Urdu literature in India had become more flamboyant, bold, and quite radical. As the cries of Inquilab Zindabad pierced the skies, some of the subcontinent’s young and gifted were trying to break away from the shackles of their own imprisoned mind.

Angaare was an outpouring of emotions much like Soz-e-Watan that preceded it. Those unbridled emotions had slowly built over time, waiting for the opportune moment to erupt. In the years following the great war, buoyed by a nationalist fervour, Urdu literature in India had become more flamboyant, bold, and quite radical. As the cries of Inquilab Zindabad pierced the skies, some of the subcontinent’s young and gifted were trying to break away from the shackles of their own imprisoned mind.

Who were these people?

In 1931, the Lady Dufferin Hospital in Lucknow had a new doctor in their ranks — Rashid Jahan. Her father, Dr. Sheikh Abdullah, a prominent member of the Aligarh movement, was the founder of the Women’s school in Aligarh, a precursor to the women’s college. A young Rashid was drawn to the writings of Jane Austen, Charles Garvice and Rashid ul Khairi, a prominent Urdu writer of his time. In 1922, while studying at Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow, she came out with her first piece of writing, Salma, a short story in the college journal. Writing wasn’t her only passion though, her work as a medical practitioner and as a proponent in the theatre circle was important in equal measure.

During her graduation years in Delhi, in the corridors of the Lady Hardinge College, she was swayed by the worker’s movement. Returning to Lucknow with a degree in M.B.B.S, she got introduced to Awadh’s ever-evolving Urdu Literary stage. There she came across a group of young thinkers just like her — Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmed Ali and Mahmood-uz-Zafar.

Sajjad was like the poster boy of Lucknow — smart, young, studying at Oxford and son of the High Court judge; he could have easily indulged in a life of luxury and grandeur, but he chose to wield the power of the pen. At Oxford, Sajjad rubbed shoulders with the likes of Krishna Menon, Mulkraj Anand and communist ideologues such as Shapurji Saklatvala, who influenced him a great deal. Returning to Lucknow in 1931 after completing his degree in law, he started his own newspaper. Sajjad’s strong ideals and modern world views won him many admirers.

After Angaare was published, the backlash was severe. Sajjad and Rashid bore most of the brunt — Sajjad for being the main instigator and the book’s chief editor and Rashid for just being a woman of her time who dared to write. Rashid had written two short stories among the nine that made up the book: ‘Dilli ki Sair’ (Trip to Delhi) and ‘Pardey Ke Peechey’ (Behind the Veil). Her narratives were scathing and it showed how women were surrounded by different layers of patriarchy and how it strangled every inch of their body and mind.

At one point, one of her protagonists from ‘Pardey Ke Peechey’, tired of the number of children she bore and miscarriages she had, said to the doctor who had come to check on her aliments –

‘As far as I am concerned, who cares if I go to hell or heaven! All that they care about is their pleasure and enjoyment. The wretched wife may live or die, all that men hunger after is their own lust’[4]

In the summer of 1931, Sajjad, having just returned from England met Ahmed Ali at a party. Ali was fascinated by the western world and Sajjad was like an oasis in a desert to him.

“Sajjad Zaheer was coming from that world, bringing with him news of it firsthand. And we found our tastes were common, a love of art, literature, music”[1]

Ali’s lineage was a stuff of legends. His family was one among five invited to India from Persia by the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan, each to perform some unique trade in the kingdom. Ali earned his laurels from Aligarh University where he crossed paths with a young Raja Rao. Rao had his eyes set on conquering the world while Ali on the other hand had to be more content with his local surroundings. In Aligarh, Ali was also acquainted with the Abdullahs (Rashid Jahan’s family) through one of the younger siblings, Mohsan.

Ali knew exactly what Sajjad intended to do with Angaare. The words were scandalous, the narrative fixated on bashing age-old dogmas and the writers themselves undaunted and ready to shock the world.

While working on the book, Rashid met Mahmood-uz-Zafar, a descendant of the Rohillah Pathan Najib ad-Dawlah from the princely state of Rampur. He was an active member of the nationalist activities while studying in Oxford. When Mahmood returned to India, he forsook his European clothes and started wearing only Khadi, the mark of rebellion.

His story Jawãnmardi (Masculinity) was an account of a male protagonist with a massive ego that could dive into any limitless chasm to satisfy itself in a society unmoving and grotesque. If you held up a mirror against it, it might have cracked.

In March of 1933, Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code was slapped upon Angaare, banning the book for good. A law which continues to be used even today and quite frequently.

We move on to November of 1934. On a cold Saturday morning, a group of people were making their way through Denmark Street in central London. Music lovers might recognize Denmark Street as London’s version of the Tin Pan Alley. In the 1930’s however, this little thoroughfare between St Giles High Street and Charing Cross Road was bustling with Chinese and Japanese food joints. The group stopped at number 4 ‘The Nanking’, their usual place. Led by Sajjad Zaheer and Mulkraj Anand, the group was greeted with muted applause as they made their way to Nanking’s cellar. Surrounded by the aroma of exotic cuisine and among a group of young eager listeners, the first drafted manifesto of Progressive Writers Association (PWA) was read out.

We move on to November of 1934. On a cold Saturday morning, a group of people were making their way through Denmark Street in central London. Music lovers might recognize Denmark Street as London’s version of the Tin Pan Alley. In the 1930’s however, this little thoroughfare between St Giles High Street and Charing Cross Road was bustling with Chinese and Japanese food joints. The group stopped at number 4 ‘The Nanking’, their usual place. Led by Sajjad Zaheer and Mulkraj Anand, the group was greeted with muted applause as they made their way to Nanking’s cellar. Surrounded by the aroma of exotic cuisine and among a group of young eager listeners, the first drafted manifesto of Progressive Writers Association (PWA) was read out.

“Radical changes are taking place in the Indian society…We believe that the new literature of India must deal with the basic problems of our existence today – the problems of hunger and poverty, social backwardness, and political subjection. All that drags us down to passivity, inaction, and un-reason we reject as reactionary. All that arouses in us the critical spirit, which examines institutions and customs in the light of reason, which helps us to act, to organize ourselves, to transform, we accept as progressive”[3]

A year later, the PWA convened their first official meeting inside the Rifa-e-Aam Club in Lucknow, a few blocks away from Victoria Street. Dhanpat Rai, who by now was going by his other pen name, Premchand, presided as the Association’s first president.

Where ‘The Nanking’ once stood now stands Regent Sounds, a music studio where the Rolling Stones put together their first album back in 1964.

Andrew Whitehead, a historian and a former BBC correspondent says:

‘When I last walked along Denmark Street, the basement of number 4 was empty. It would be such a pity if this historic location was lost.’

The Rifa-e-Aam Club has also lost its charm. Once a nationalist den, now it will hardly give you any sense of its fabled past. The last time I visited, its outer facade was crumbling. Its hall, which bore witness to historic pacts and some rousing speeches, now stays stoically dormant.

Did the progressives fare any better though?

Writers like Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chander, Sadat Hasan Manto all joined the movement from time-to-time adding fuel to an already raging fire but the people who sparked it never got back together.

A bitterness had already grown between Ahmed Ali and Sajjad Zaheer by the time of the PWA’s first meeting in Lucknow. By Ali’s own admission the very idea of progress was what drew a line between the former friends!

“For Sajjad Zaheer, progress meant standing still, looking at things only from one very orthodox, narrow point of view. You cannot narrow progress”[1]

As for Rashid and Mahmood, they got married and joined the communist party. Though they kept on writing for some time, party and political work eventually became more important to them.

To a large extent, the PWA by itself and also through some of its offshoots did succeed in achieving its goal in introducing a new kind of literature. Various actors of the movement made their names particularly in the early post-independent decades of the Bombay film industry. Sahir Ludhianvi, Asrar ul Hassan Khan a.k.a Majrooh Sultanpuri and Kaifi Azmi were household figures and their work in films like Naya Daur, Teesri Manzil, Apna Haath Jagannath proudly carried the tag of the progressives. In Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Saat Hindustani starring Utpal Dutt, A.K Hangal and a certain debutant Amitabh Bacchan, Kaifi wrote

“Zulm hadd se badhyega toh ghatt jayega

Apni talwar se aap kat jayega”

(If oppression rises beyond limit, it will fall. By it’s sword, it will bleed.)

The film won the national award for best lyrics.

The flame ignited by a group of young daring writers way back in 1932 still lingers on, even in our times. In different quarters of society, universities, cafes, libraries, books shops, you might hear whispers or animated discourses on them as their inflammable words continue to inspire people.

Like an ember that burns in perpetuity.

Sincere gratitude to Mr Andrew Whitehead for answering our queries regarding ‘The Nanking’ which played a very pivotal part in the formation of the PWA.

- Ali, Ahmed, and JSAL. “INTERVIEW : AHMED ALI: 3 AUGUST 1975 ROCHESTER, MICHIGAN.” Journal of South Asian Literature 33/34, no. 1/2 (1998): 117-94. Accessed September 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23234237.

- Alam, M. (2020, July 31). The ‘DEMISE’ of Nawab Rai and the birth OF Munshi Premchand. The Wire. Retrieved September 17, 2021, from https://thewire.in/books/premchand-birth-anniversary-pen-name-story.

- Ahmed, T. (2018). Literature and Politics in the Age of Nationalism: The Progressive Writers’ Movement in South Asia, 1932-1956. (dissertation). ProQuest. Retrieved September 11, 2021, from https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/33736/1/11010508.pdf.

- Chauhan, V. S., & Dalvi , K. (Trans.). (n.d.). Buy angarey: Nine stories and a play book online at low prices in India: ANGAREY: Nine stories and a Play reviews & ratings. Buy Angarey: Nine Stories and a Play Book Online at Low Prices in India | Angarey: Nine Stories and a Play Reviews & Ratings – Amazon.in. Retrieved September 11, 2021, from https://www.amazon.in/Angarey-Stories-Vibha-S-Chauhan/dp/8129131080/ref=pd_lpo_2?pd_rd_i=8129131080&psc=1.

- SAIDUZZAFAR, HAMIDA. “JSAL Interviews DR. HAMIDA SAIDUZZAFAR: A Conversation with Rashid Jahan’s Sister-in-law, Aligarh, 1973.” Journal of South Asian Literature 22, no. 1 (1987): 158-65. Accessed September 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40873940.

- Whitehead, A. (2016). Downstairs at the NANKING restaurant. ANDREW WHITEHEAD. Retrieved September 11, 2021, from https://www.andrewwhitehead.net/blog/downstairs-at-the-nanking-restaurant.