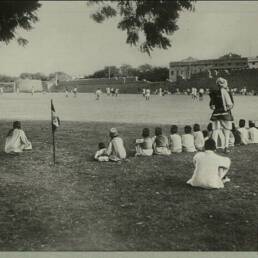

The photo in this article shows a group of Indian soldiers posing in front of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, China. It was taken a couple of days after British and Indian soldiers stormed the Forbidden City, demanding the surrender of the Chinese regime.

During the wee hours of 15 August 1900, commotion besieged the Imperial City, which lay at the heart of Beijing, China. With the enemy at the gates, Yehe Nara Xingzhen, aka the Dowager Empress Cixi, fled the city with most of her court in disguise.

A couple of hours later Adna Chaffee, commander of American troops, ordered his men to blast through the walls and occupy the Imperial City.

Assisted by German, Japanese, and a couple of thousand Indian artillery and cavalrymen, the alliance forces were finally able to occupy the Imperial City, thus bringing to an end a bloody rebellion.

But what were Indian troops doing deep in the heart of China? And what of this rebellion?

In the late 19th century, rural China was riddled with hardships. Trade concessions granted to foreign powers by the ruling Qing Dynasty disgruntled the local populace who rose to rebel. Foreign dignitaries and Christian missionaries were targeted and it quickly spread around the country.

Leading the uprising was a Chinese society called Yihetuan, whose disciples fought mainly with their fists, which to the Western eye looked like boxing. By the end of May, the ‘Boxers’ had forced most of the foreign dignitaries to take refuge in the capital where they called for aid.

An eight-nation alliance was formed and a strong force was quickly dispatched to deal with the ‘Boxers.’ Aiding the alliance were a considerable number of Indian troops who were sent as part of the British Empire.

Leading the charge was Lieutenant-General Sir Alfred Gaselee, a British officer of the Indian Army. By July, a full-blown invasion was taking place as the alliance forces were determined to make short work of the rebellion by quickly taking control of Beijing.

Exhaustion and changing temperatures, however, led to the death of many while on the road to Beijing, The Indian contingent, however, fared a lot better than their European counterparts in those trying situations.

Furthermore, they were well cared for by their superior officers. They were given proper equipment, clothing, and ration to survive the harsh conditions. By the time the siege of Beijing began, the Indian regiment was at the forefront of the attack.

By mid-August the capital was taken, with the court and empress gone into hiding. The Chinese Imperial forces, led by the Empress’s own personal guards, fought valiantly but were eventually overpowered.

The rebellion officially ended in September 1901, with a peace treaty signed between the alliance forces and the Empress. The treaty allowed foreign troops to be stationed in the capital region, which led to Indian soldiers also staying there.

Thakur Amar Singh, part of Jodhpur Lancers, recalled in his diary his experiences in the region: “The Great Wall was our daily view, I had walked for weeks continually on it and was wondering what sort of man he must have been who started this enormous work.”

By the end of their postings, many of the soldiers spoke fluent Mandarin. But all was not well. As soon as the rebellion subsided, things turned ugly. In many districts, the Boxers were subjected to horrendous torture and summary execution.

Then there was the looting. An American journalist posted in China said this about the occupation of Beijing – “the biggest looting expedition since Pizzaro.” The looting was unprecedented and Gaselee even created a system where the looting was auctioned at the British Legation Quarter.

It is unclear whether the Indian contingent also took part in these lootings but their superior officers didn’t hold back. A curious case emerges about two golden bells taken from the Temple of Heaven by two British army officers.

C. E. Thornton, commanding officer of the 16th Cavalry, ordered the bells to be taken back to India as regimental trophies. Later on, demands were made to restore it back to the temple.

The British government at the time, however, decided that the bells were found in a rubbish heap which didn’t amount to looting, so they kept hold of it. They stayed in India till 1994 when unconfirmed reports suggested that they were returned to China by the Indian government.

The Indian regiment’s role in the Boxer Rebellion spurred Indian soldiers to join the British-Indian Army for a regular source of income and also for the chance to move around. In time, they became an effective tool of warfare.

Sources

The Boxer Rebellion, National Army Museum, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/boxer-rebellion#:~:text=In%201900%2C%20British%20and%20Indian,and%20their%20Imperial%20Chinese%20allies; THE INDIAN EMPIRE AT WAR: From Jihad to Victory, The Untold Story of the Indian Army in the First World War by George Morton-Jack;