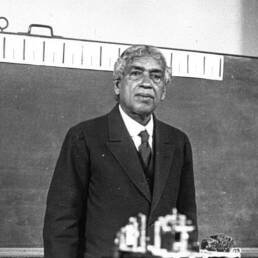

Rarely do we come across a body of work that is all-encompassing, influencing culture and society at its deepest core. Ramaswamy Krishnamurthy was an art critic, novelist, freedom fighter, and lyricist all in one. Some of you might know him as ‘Kalki’.

In the early 1930s, a young M. S. Subbulakshmi moved to Madras from her hometown of Madurai to sing in concerts. Her gramophone records were selling well, but her mother wanted her to sing in concerts, that men dominated in those days.

Her voice regularly attracted the elites of the Madras Society. Among the regular visitors was a man called Ramaswamy Krishnamurthy who was at the time running a weekly critics column called aadal paadal (song and dance) for a magazine called Ananda Vikatan.

Krishnamurthy visited theatres, and concerts, writing and jotting down notes, seeing artists from a critical point of view, and later presenting his thoughts in a literary format appealing to a mass audience.

India was going through a period of political and cultural awakening. On one hand, you had people led by the national leaders toiling against imperial forces, on the other, with the coming of the talkies, the world of theatre, cinema, and singing were breaking new ground.

The world of cinema and its varied potential to influence culture as a whole awed Krishnamurthy. In 1939 he wrote in an article: “We will keep talking about the ills done to the world by cinema. But, as we hear that a good film is being released, we are only too willing to spend our money…”.

But why should we be talking about Krishnamurthy in the first place? Born In 1899 at Puthamangalam village in Tanjavur district, Ramaswamy Aiyar Krishnamurthy became embroiled in the freedom struggle early in life.

In 1922, he met T Sadasivam while spending time in Tiruchi jail as a political prisoner. After being released, he worked with the Inc and closely with Rajaji (C. Rajagopalachari), but Krishnamurthy was destined for a literary path.

A year later he joined the Tamil magazine Navasakti where he would take his first steps toward journalism and critical reviewing. A couple of years later he joined Ananda Vikatan where he would start writing under various pseudonyms, ‘Kalki’ being one of them.

He started reviewing music and dance concerts. His column for Ananda Vikatan, Aadal Paadal was laced with humor and was considered to be nothing less than the gold standard when it came to critical analysis of artists and their performances.

Krishnamurthy’s foray into the literary world came at a moment when Tamil culture was going through a transformation. There was a time when the Tamil language was considered unsuitable for Carnatic music and the belief was questioned in the early 1940s.

An announcement appeared in The Hindu dated 28th July 1941 under the caption “Encouragement of Tamil Songs”. The Annamalai University Syndicate had “approved a scheme for the composition of new Tamil songs and the popularisation of old songs”.

In August, of the same year, a conference with prominent Carnatic musicians was held proposing ways to popularise Tamil songs. This opened a pandora’s box and fights erupted across the Tamil literary and art world.

Together with Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar, and R.K. Shanmugam Chetty, Krishnamurthy became a staunch supporter of the Tamil Isai Sangam. He regularly wrote columns in his newly formed magazine ‘Kalki’ to have more Tamil songs included in music concerts.

Soon Kalki became eponymous with whatever was significant in Tamil culture, Krishnamurthy used his various pen names to fight against various societal ills like untouchability and violence against women.

Through Kalki, Krishnamurthy’s various talents poured out like an unstoppable train. Short stories, novels, and critical reviews, Kalki was an instant hit and it was because of Krishnamurthy’s relentless quest to put Tamil literature and art on a pedestal.

Solaimalai Ilavarasi, Sivagamiyin Sapatham, and Parthiban Kanavu are just some works which showcase Krishnamurthy’s literary and creative prowess. Though he left us at the young age of 55, his body of work continues to inspire many.

Ponniyin Selvan, the historical novel, is considered to be one of Krishnamurthy’s finest works and stalwarts like MGR and Kamal Hasan had tried unsuccessfully to adapt it for the big screen, until Mani Ratnam’s version came out only this year.

Sources:

- Stephen Putnam Hughes, Music in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Drama, Gramophone, and the Beginnings of Tamil Cinema, The Journal of Asian Studies , Feb., 2007, Vol. 66, No. 1 (Feb., 2007), pp. 3-34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20203104;

- J. THYAGARAJAN, Tamil : the Printed Word, Indian Literature , January-February 1976, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January-February 1976), pp. 69-74, Sahitya Akademi, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24157248;

- Amanda Weidman, Gender and the Politics of Voice: Colonial Modernity and Classical Music in South India, Cultural Anthropology , May, 2003, Vol. 18, No. 2 (May, 2003), pp. 194-232, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3651521;

- S. SANKARANARAYANAN, Patriot, writer, and art critic Kalki Krishnamurti, https://www.sruti.com/index.php?route=archives/heritage_details&hId=68