Man, his best friend and a mercy run to stall an epidemic

In December, 1924, a remote Alaskan town was facing a deadly outbreak of diphtheria. It was a harsh winter; the sea route to the rest of the world was closed and would not open until July. The town had no supply of diphtheria antitoxin when the epidemic broke out. Without the antitoxin, it was feared, the fatality rate would be 100%. That’s when the heroes stepped in – 20 brave men and 150 of man’s best friends undertook a perilous journey that saved the tiny town from certain disaster.

By Trinanjan Chakraborty

About two degrees south of the Arctic Circle lies the tiny town of Nome. It was incorporated in 1901, during the heady days of the Gold Rush when the population had swelled to 20,000. Those glory days were long gone and by 1924, Nome was home to around 1500 people of whom 455 were Alaska natives and the rest were of European descent.

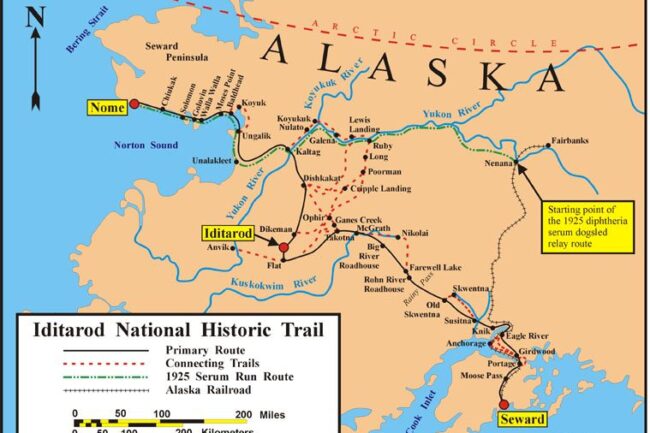

The town was dependent on the sea link with the port of Seward in the southern peninsula for mails and provisions. However, from November to July, the Bering Sea route was icebound with the Nome harbor iced up. The only connection for the inhabitants of Nome with the rest of the world was the 674 km long and torturous trail which started from Seward port, traversed multiple mountain ranges, the vast span of the Alaska Interior before arriving at the Nome region.

In December, 1924, the town of Nome had only one serving doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch who helmed the local hospital and was assisted by four nurses. The hospital had 25 beds. Much earlier, when the sea link was functional, the hospital’s entire stock of Diphtheria antitoxin was past its expiry date. Dr. Welch, on noticing this, placed an urgent order for replenishment. Unfortunately the replacements did not arrive by November when the sea route closed down for nearly nine months. Dr. Welch may have been a tad concerned but there is little to suggest that he had any idea of the impending peril that was to engulf the tiny town and its inhabitants.

That December, Dr. Welch received a few young patients with complaints of a sore throat. He diagnosed them to be cases of tonsillitis and treated them accordingly. However, over the next few weeks, the cases grew at a rapid pace. And then, news came that four children with symptoms had succumbed to the disease. Dr Welch was by now stricken with fear. He was nearly certain that the worst had come true: an outbreak of diphtheria had hit the town when it had no medicine for the disease. His doubts were confirmed when in the middle of January 1925, he definitely diagnosed diphtheria in a three-year-old boy who sadly died within a couple of weeks. In desperation, Welch tried the expired batch of antitoxins on his next patient, a seven-year-old girl. The girl died a few hours later.

Dr. Welch now knew that they were facing impending doom. He informed the town’s mayor and an urgent city council meeting was convened which announced a strict quarantine/lockdown in the town on January 21, 1925. The very next day, the town’s mayor, Major Maynard sent out a telegram to the US Public Health Service in Washington DC requesting immediate succor. His message read:

AN EPIDEMIC OF DIPHTHERIA IS ALMOST INEVITABLE HERE STOP I AM IN URGENT NEED OF ONE MILLION UNITS OF DIPHTHERIA ANTITOXIN STOP MAIL IS ONLY FORM OF TRANSPORTATION STOP I HAVE MADE APPLICATION TO COMMISSIONER OF HEALTH OF THE TERRITORIES FOR ANTITOXIN ALREADY STOP THERE ARE ABOUT 3000 WHITE NATIVES IN THE DISTRICT.

Despite the quarantine being put in place, by the last days of the month, the number of confirmed cases of diphtheria in the town touched 20 with another 50 suspected cases in Dr. Welch’s estimation. The region surrounding Nome was estimated to have a population of close to 10, 000. Without antitoxin, this entire population was vulnerable to succumb to this deadly pandemic.

The situation was as bleak as it gets. The sea route was out of bounds. Those were nascent days of commercial aviation. But there were only three planes available in the region and these were vintage Standard J biplanes which were of “open-cockpit” type and had water-cooled engines. In the freezing temperatures and harsh winds of the Alaskan winter, they were rendered unusable. The Alaskan Railroad route didn’t reach anywhere in the vicinity of Nome. The closest railroad was Nenana – nearly 700 miles away. Traversing that distance in the Alaskan outback was daunting even in the best of weather. In those severe winter months, it was near suicidal.

The distraught mayor, Major Maynard, pushed for flying in the antitoxin but this idea was quickly vetoed by the Public Health Service. The breakthrough idea came from Mark Summers of the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields. Summers proposed the use of two dog-sled relay teams. One team was to travel from Nome and the other from Nenana and meet about mid-way at Nulato. The normal running time for the Nenana to Nome trip was 30 days while the record time ever achieved was 9 days. According to Dr. Welch, in the brutal conditions of the trail, the antitoxins were unlikely to last more than 6 days at best so the record had to be broken if the plan was to succeed.

Just when things couldn’t get any worse, they did. A high pressure system in the Arctic resulted in 20-year record low temperatures in the Interior. In addition, another system had formed in southeast Alaska and was burying the region in 10-foot snow. Across the Alaskan Interior, most forms of transport were suspended. At the end of January, Fairbanks registered a temperature of -46 °C.

It is said that the human spirit finds a way when all seems lost. Something like that happened then with a hero stepping up. Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian sled dog breeder and a former gold chaser[1], was an employee of the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields. He held the record for the sled run from Nome to Nulato (4 days) and had won the all-Alaska Sweepstakes thrice. His rapport with his Siberian huskies, especially his lead – the 12-year old Togo, had become something of a legend. Seppala was now selected to lead this audacious plan.

The immediate supply available in the region of diphtheria antitoxin was 300,000 vials with the Anchorage Railroad Hospital. This first supply was expected to help ward off the initial wave of the pandemic till larger supplies arrived from Seattle by sea. The supplies arrived at Nenana on January 27 1925. The governor of Alaska, Scott Bone, ordered the best mushers[2] and sled dogs available in the region be tasked for the job. Many mail carriers, best adept at handling the treacherous route, were selected. The first of the drivers was “Wild” Bill Shannon who covered the first leg of the journey losing around four of his dogs and had his face blackened by frostbite when he completed the 52 miles mostly in temperatures lower than – 40 °C. He had started the great run on the night of January 27.

Seppala was initially chosen to anchor the final leg but then the authorities decided to put him in charge of the most treacherous section of the run. At 91 miles, it was nearly twice the distance of any other carrier. But he had a deep personal stake as well. His family, including his eight-year-old daughter, was in Nome and at great risk. Seppala with his trusted dog Togo leading the pack covered the stretch between January 27 and 31, handling some of the worst weather and travel conditions imaginable. The weather was decent when we started from r Nome (−29 °C) but would turn harsh touching −65 °C.

The supply reached Nome at 5 A.M. Alaska Time on February 2. Anchoring the final leg was Gunnar Kassen. His journey was nearly destabilized by a ferocious blizzard but Kassen and his dogs held firm. It is said that the first words Kassen spoke to his welcoming committee were “Damn fine dog” in reference to his lead, Balto, before he collapsed into unconsciousness from fatigue.

Together, all the drivers had covered the 674 miles in 127 and a half hours, considered a world record. The entire journey was done in extreme subzero temperatures with near-blizzard conditions and hurricane-force winds. Several of the dogs died during the trip. It was a classic demonstration of the saying “nothing is impossible.” The incredible relay came to be known as the Great Serum Run.

The sled drivers who took part in the relay would soon become famous, thanks to the growing popularity of radio in the USA. The desperate race was covered in almost real-time by newspapers and radio with New York Times running the famous headline “Serum relief near for stricken Nome. And blizzard delays Nome relief dogs in the final dash.” All of the mushers received letters of recommendation from President Calvin Coolidge. The Senate stopped work as a mark of respect to the men and their pets who had literally braved hell to save the lives of thousands. Gunnar Kassen, who worked under Seppala in the gold mine, toured the west coast for over a year with his dogs. His lead dog Balto became a celebrity in his own right with a bronze statue of him unveiled in New York in December 1925. Kassen repeatedly alluded to Balto’s heroics in his interviews to the press. But the animals which probably gave it maximum were Seppala’s pride possessions: Togo and team. In comparison to the 55 miles run by Balto and his team, Togo and team ran an incredible 260 miles[3].

When the first consignment, good enough for treating 30 patients, reached Nome, the active case count was 28. Soon, a larger consignment arrived, again brought over by sled relay involving many of the drivers and dogs involved in the first one. By the end of February, life had returned to near normalcy in Nome and the quarantine was also lifted.

Many heroes: man and dog, saved the lives of thousands of men, women and children through an unbelievable act of courage. Today, as the entire world is recovering from the onslaught of a terrible pandemic, it is an apt time to remember and pay homage to them.

Notes:

- Prospector in search of mines/deposits of gold or other precious minerals

- Mushing is a sport or transport method powered by dogs. It includes carting, pulka, dog scootering, sled dog racing, skijoring, freighting, and weight pulling. The drivers of these transports were known as “mushers.”

- While the allotted relay distance of Seppala and his team was 91 miles, they had to travel 170 miles from Nome to arrive at their starting point.

References:

- Wertheim, Jon. “A Century Ago: Another Epidemic-and an Improbable, Furry Solution.” Sports Illustrated, Sports Illustrated, 13 Jan. 2021, www.si.com/more-sports/2021/

01/13/alaska-serum-run-1925- togo-not-balto. - Earth, B., 2016. BBC One – Planet Earth II. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20161014-in-1925-a-remote-town-was-saved-from-lethal-disease-by-dogs> [Accessed 23 October 2021].