Four decades ago Calcutta witnessed the bloodiest day of Indian football. We relive the fateful day through first-hand narratives of those who lived through the nightmare.

By Trinanjan Chakraborty

Saturday, 16th August, 1980. Calcutta. The Mecca of Indian sports. The city whose heart beats for the beautiful game. The day couldn’t get any bigger. Archrivals Mohun Bagan and East Bengal were squaring off in a “Calcutta Derby” at the Eden Gardens. Being a League encounter, the result was always less significant in the long run, for supporters of either side, however, a victory meant bragging rights. And thoughts of defeat were never entertained.

Neel Madhab Dutta was a young man in his early twenties, a die-hard supporter of East Bengal. If there was a football match involving the Red & Gold brigade, he was a permanent fixture at the ground. That day was no exception. The season had not started well – several big names had left East Bengal for Mohammedan Sporting. But the arrival of three Iranian recruits, especially a mercurial young man named Majid Bishker had infused new hope among the East Bengal faithful. And Pradip Kumar Banerjee, the man who had led the Red & Golds to unprecedented success in the first half of the preceding decade, was back in charge.

As the match progressed, nothing seemed unusual. Like most derbies, it was a tense affair with tempers rising and the gallery also getting worked up. And then suddenly, it was like a scene straight out of the Walking Dead.

More than 40 years later, the first thing Dutta recalls is the unbelievable volume of bricks and stones that appeared as if magically. Soon, the two sets of supporters got into a free for all melee, baying for each other’s blood. He remembers being thrown on to the floor and surviving a stampede albeit without shoes, in torn clothes, and several cuts and bruises. Dutta somehow regained his feet and the sight he witnessed stunned him. In one of the adjacent stands, the Ranji Stadium- several fans, trying to escape the madness, were jumping down from the top tier to lower levels. Terrified and in pain, Neel Madhab Dutta’s survival instinct kicked in. He climbed to the top most level and sat there well into the evening – long after the match was over.

When he finally got down and reached the exit, the first sight that greeted him was piles and piles of abandoned footwear and the cries and moans of injured fans. In the darkness, the sound of those moans left the young man traumatised. Dutta saw an agonized old man crying out for his young missing nephew. He recalls walking barefoot from the Eden Gardens to Sealdah station, still in shock and daze. Dutta never attended another football match in his life although he retained a keen interest in the game.

16th August, 1980. The darkest day of Indian football. The day when the beautiful game turned deadly – leaving sixteen dead, countless injured, and families shattered. What happened that day? Why did a football game turn into such unrestrained violence? How did common people, who thronged the ground for the love of football suddenly become so savage with passion? To answer these questions, we need to travel back to over a hundred years to understand the factors that shaped Bengal and Bengalis’ relationship with the beautiful game and what ultimately led to that devastating derby.

Chapter 1

Play audio to immerse into Calcutta Maidan's of electric atmosphere

1877. A carriage bearing a rich Indian lady and her son was passing through Red Road, Calcutta. In the adjacent ground, European soldiers were playing a game of football. The boy was enthralled – he pleaded with his mother to stop the carriage so he could take a closer look. The lady finally relented. As the boy watched from the sidelines, the ball rolled out of play towards him and a soldier asked him to kick it back in play. That kick has been immortalized for posterity as the first time ever a Bengali kicked a football – the reality may have been a little more humdrum and a little less dramatic. But the impact this boy would go on to have on the game of football and its spread across Bengal would be no less than legendary. Nagendra Prasad Sarbadhikari – that was his name – would legitimately fall in love with the game and in time come to be acknowledged as the “Founding father of Indian football.”

But Sarbadhikari was not the only Bengali to have a profound effect on this game. Before he gained global fame as a spiritual leader, Narendranath Dutta was better known as an avid sportsman. One of the most enduring myths of the Calcutta maidan is how, as a young man, he took seven wickets in a cricket contest against a European side. As he grew up, Swami Vivekananda became a strong proponent of physical excellence. Indians in general and Bengalis, in particular, were perceived as weak and effeminate. Vivekananda wanted to change this perception. Himself an avid practitioner of wrestling, bodybuilding, boxing and horse-riding among others, the great man also exhorted his brethren to follow suit. From his lips emanated the famous clarion call, “You will be nearer to heaven through football than through the study of the Gita. You will understand the Gita better with your biceps, your muscles a little stronger.” – There couldn’t have been a more profound pep talk.

Football in Calcutta grew exponentially in the last decade and a half of the nineteenth century. Sarbadhikari’s Sovabazar Club was the first torchbearer of the Indian (Bengali) community’s footballing aspirations, waging lone battles against the European hegemony of the city’s football. Gradually, more followed in his wake. Manmatha Ganguly’s National Association, Sir Dookhiram Majumdar’s Aryan Club, Kalicharan Mitter’s Kumartuli Park and Mohun Bagan Athletic Club (formed by three aristocratic North Calcutta families) all came up, as football became a symbol of expression against the shackles of foreign rule. Though success on the field was rare – a combination of lack of experience, biased officiating, poor infrastructure (most native teams played barefoot) – that didn’t deter the zeal in any way.

As nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, the nationalistic fervor in Bengal kept rising. Lord Curzon’s infamous Bengal Partition Act added fuel to fire. All over the province, sports clubs became a front for the armed insurgency movement. The football grounds also saw tempers rising. “Gorer math-e Gora petano” (beating up players and supporters of European clubs at the Maidan) became a way for Bengali young men to level up with their colonial masters and their oppressive rule.

July 29th, 1911 – a day that has now entered the annals of Indian football history. In the final of the IFA Shield, eleven Bengali men defeated East Yorkshire Regiment – a British side. Although it was not the first time an Indian team had defeated a European one (Sovabazar is believed to be the pioneer), the high-profile nature of the game and the staunch nationalistic sentiment that pervaded every sphere of life made this a landmark incident and a slap in the face of the mighty British Raj. It was a strike back of justice for a century-and-a-half of oppression – dating back to Clive’s treachery on the Nawab of Murshidabad and right up to Curzon’s malevolent plans of bifurcating Bengal.

Even as the nationalist movement raged on, football clubs kept sprouting up across Calcutta. In 1920, Jorabagan Club was facing Mohun Bagan when one of Jorabagan’s best players, Sailesh Bose, was inexplicably left out of the starting eleven. One of the leading functionaries of the club, Suresh Chaudhuri felt infuriated at this and soon left Jorabagan. He, along with some of his close friends, formed a new football club. As the founding members all hailed from the eastern part of Bengal, the new club came to be christened “East Bengal” club. They say that the flow of time is like a stream, smooth in general but capable of rising into big waves when pebbles and stones are thrown in. Probably, no one realized it then, but this moment was akin to a gigantic boulder being dumped into the time stream of Bengali history.

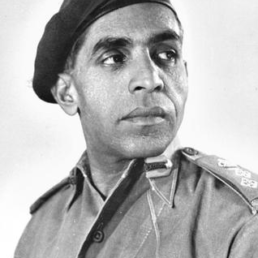

Jyotish Chandra Guha better known as “JC” Guha, is an iconic name in the annals of East Bengal club. Having represented the club as a goalkeeper in the 1930s, he later on became a secretary of the club and also its unofficial coach / manager during the mid to late 1940s. He held the post of club secretary for well over two decades and had an umbilical connection with the club.

On that day, 16th August, 1980, seated in the stands was someone who came from the famous Guha stock. Anindit Guha was barely sixteen. Born to love East Bengal, he was eagerly looking forward to the clash. But a sight he saw that day would come to haunt him forever. As fights broke out in the stands of the Ranji Stadium, he watched with shock as a man was pushed over the edges several feet down into the tier below. It mentally scarred this young man forever. He vowed never to step inside a Calcutta stadium for a football match ever again. More than 40 years later, even though his passion for East Bengal remains unwavering, he has not budged from his vow. He watched his beloved Red & Gold take the field in matches outside Calcutta but never did he again step inside the ground in Calcutta. One can only imagine the horrors that the day inflicted on this young mind.

Twelve-year old Ajay Pal worked in the canteen at the New Secretariat building for meager wages. He had bought a ticket to the Ranji Stadium worth 60 paise for six rupees in the black market. That evening of the match, Pal was among the missing.

But that terrible day exacted a far worse price from people even younger. Twelve-year old Ajay Pal worked in the canteen at the New Secretariat building for meager wages. He had bought a ticket to the Ranji Stadium worth 60 paise for six rupees in the black market. That evening of the match, Pal was among the missing. His father’s heartrending shouts filled the corridors of the SSKM Hospital. And they weren’t the only ones. Thankfully, Pal was subsequently located, battered and bruised but alive at Shambhu Nath Pandit Hospital.

But some had it worse even without stepping inside the ground.

In 1980, Goutam Ghosh was another young man in his early twenties – on the verge of stepping into the next phase of life. A regular at the ground to cheer for his beloved Mohun Bagan, for some reason he missed the match that day. His world turned upside down with a phone call from his best friend’s parents in the evening, enquiring about the whereabouts of Pradipta, his friend. Ghosh knew what Pradipta’s worried parents did not – his friend had gone to Eden Gardens for the match. And now he was untraceable. After more than 40 years, it is an emotional struggle for Ghosh to recall what followed in the coming hours. He remembers rushing to Bhowanipur police station and being directed to the morgue of SSKM Hospital where most of the casualties had been brought in. One after another, the white covers were removed to show him the victim’s faces. It was an experience that no one would wish on their worst enemies. Thankfully, Goutam Ghosh’s story had a happy ending. Pradipta returned home late that night.

But Howrah’s Dhananjay Das’s family was not among the fortunate. Das, who ran an automotive business, was crazy about Mohun Bagan. Once, he left home for Bombay informing family that it was a business trip. It was only when he returned that they came to know he had gone to watch his favorite club compete in the Rovers Cup. That fateful day too, he was present at the doomed Ranji Stadium. His family did not know but when he did not return late in the evening, they started getting worried. Unbeknownst to them then, Das was one of the thirteen corpses whom Goutam Ghosh had checked while searching for his missing friend. His unrequited love for the game and his club had extracted too steep a price.

1947 – No single year has had as dramatic an impact on the history of the subcontinent as this. Long awaited and precious independence came at the cost of partition of the country. Bengal was one of the two provinces (other being Punjab) which suffered the most due to this. The human cost of partition was unimaginable. The Muslim dominated eastern districts became East Pakistan. It sparked one of the largest human migrations in documented human history. By 1951, according to Census data, 4, 33, 000 Hindu refugees from East Pakistan had arrived in Calcutta. This number kept increasing as the years went by. The state they were coming to was but a poor and cheap imitation of what was once the richest province of entire Asia. The war years, the famine of 1943, the riots of 1946 had left Bengal ravaged. The partition was another killer blow. The agriculturally rich eastern districts now were no longer a part of India, badly hitting the supply line for industries like jute. Burgeoning population aggravated by industrial decline presented a nightmarish situation.

Added into this volatile mix was the refugee influx leading to heightened socio-cultural tensions. There was a long-standing cultural divide between the populations of eastern and the western part of Bengal. In some ways, Kipling’s “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” well describes this divide. Till the partition, this divide, although real, remained somewhat subdued. But post 1947, this became a pronounced reality. Both sides held a narcissistic view of cultural superiority. The people of western Bengal, called Ghotis by their eastern counterparts, looked upon their brethren from the east as loud and uncouth, not worthy of being on the same pedestal. On the other hand, those from the east, referred to as Bangals, disparaged the Ghotis as petty, lazy and mean-minded, among others. A common derogatory remark by the people of west Bengal for the refugees was the sign of barbed wire on their backs – an insensitive playback on the movement from east to west post partition.

Most of the refugees had lost all their wealth and life’s savings while fleeing from East Pakistan. These homeless people thus became suspect to the original residents.

This evolving socio-political situation also had a dramatic effect on Calcutta football. The rivalry between Mohun Bagan and East Bengal in pre-Independence Bengal wasn’t exactly about brotherly love. There had been clashes between their supporters. However, partition and the massive refugee influx dramatically altered the status quo. For the refugees from East Bengal, who suffered the most ignoble of horrors, having lost everything and leading a miserable existence now in refugee-camps and colonies, the East Bengal football team became a symbol of hope, a window of escape to utopia. Their love for the football team now became an inseparable part of their identity. This period also saw a remarkable ascendancy for the club with the coming together of five incredibly talented forwards – orchestrated by the legendary JC Guha – dubbed the Pancha Pandavas. As East Bengal’s fan following rose dramatically, the original residents of west Bengal, who formed the core support base of Mohun Bagan, felt threatened and entrenched themselves deeper into the club that symbolized their very existence and culture. A rivalry deep-rooted in racial difference, one to rival the Old Firm of Scotland, thus took shape.

Play audio to immerse into the vintage era of radio commentary

Corruption had by then become a feature of all walks of life in the state. Black marketing of tickets for sports matches was a most profitable initiative. Garfield Sobers’ West Indies were playing the New Year test at Eden Gardens. The ground was overflowing with people. More than 20, 000 duplicate tickets had been sold and there was no place to even stand inside the stadium. Spectators started crossing the boundary line and milling onto the field. Used often to quell public protests in the most brutal manner, the police by then had become accustomed to going trigger (or lathi) happy at any given opportunity. That morning, their weapon of choice was the bamboo stick.

As a senior spectator collapsed in a pool of blood, all hell broke loose. Bamboo poles were uprooted and irate spectators chased cops and started beating them up. The canvas roofs of the stands were set on fire, police charged tear-gas and it got unbelievably ugly. Outside the stadium, buses were torched, shops had their windows smashed. Several of the West Indian players went and took shelter in the Mohun Bagan tent for safety. Fast bowler Charlie Griffith lost his way and ran all around the Maidan before arriving at the team hotel (Grand), on the verge of collapse. The image of West Indian Conrad Hunte climbing the stands to save the national flags from burning down became one for the ages1.

Sadly though, far from being an eye-opener, this behavior from the upholders of law and order became a norm. A few years later, for an India/Australia test match, there was a mad rush for tickets as the counters opened. The police started violently lathi charging, a stampede broke out and soon six people lay dead. Even this immense tragedy didn’t open any eyes as we were to learn a decade later.

On that dark day of August, 1980, as the D block of the Ranji Stadium erupted in violence, the cops sat back coolly, watching the game. Ever since the first United Front government came to power in the state in 1967, the police force had become accustomed to orders of “staying-out” of trouble between establishment owners and trade unions2. This inertia had ended during the tumultuous five years of Congress rule in the seventies when the police force had effectively functioned as a private militia of the government. When the Left Front government came to power in 1977, police action (or lack of it) gradually became remote controlled from the men in power.

That day too, only when the match was nearly over, did they descend in full vigor, raining blows a dozen a minute on the spectators. A mad stampede erupted and people were crushed beneath a scared crowd desperately trying to get out and save their lives.

Chapter 2

Play audio to immerse into the unfortunate scenes on the fateful day

Deepak Majumdar was a young man of 25 in 1980. He belonged to a rare breed – a proud “Bangal” (East Bengali origin) but a ferocious supporter of Mohun Bagan. Holding a ticket to Ranji Stadium, he was frustrated as he was late in reaching the ground and found the “good” seats all taken. Left without a choice, he, along with his friend, climbed towards the topmost section. Looking back, he feels that delay probably saved his life. As he saw scenes of violence that he could scarcely believe, Majumdar and his friend stayed rooted at their perch, daring not to move out of fear of their lives. A sight he saw has haunted him since. Amid the fracas, an unfortunate soul was pushed from the top tier, hurtling through the air into the lower stand. Several more jumped, voluntarily, just to save themselves from the deathly dance that engulfed the Ranji Stadium. After so many years, the horrors of that afternoon haven’t left Majumdar.

Majumdar and his friend stayed rooted at their perch, daring not to move out of fear of their lives. A sight he saw has haunted him since. Amid the fracas, an unfortunate soul was pushed from the top tier, hurtling through the air into the lower stand.

Alok Chatterjee was a top sports journalist of the time with a leading Bengali news daily. What unfolded that day, while saddening, did not surprise him. In his opinion, since the late 60s, spectator behavior and police and administrative callousness were only building up to such a tragedy. During that ill-fated visit by the Australian cricket team in 1969/70, an embarrassing incident had taken place. One of the Australian team members, Doug Walters was conscripted in the Australian armed forces. A false rumor spread that Walters had been on tour to Vietnam. Hundreds of young men, fuelled by Communist ideals, besieged the Australian team hotel in protest, throwing stones at the windows and vandalizing nearby shops. When the Australian team bus was journeying towards the airport after the match, it was subjected to stone pelting near the city center.

Even after so many years, Chatterjee remains scathing in his assessment of the police and holds them primarily responsible for the horrors that unfolded that day. Interestingly, it is a sentiment shared by the then police commissioner of Calcutta, Nirupam Som who was unrestrained in criticizing his own force for their incompetence on that day.

Very few countries or states have suffered as much tumult as West Bengal did in the years post-independence. But it took on a whole new life of its own since 24th May 1967. The next decade in the history of the state was of agony and bloodshed. First came the Naxalbari uprising which started off as a rural movement but soon found most vocal support amongst Calcutta’s colleges and universities. It was followed by events across the border. Since the early 60s, voices for autonomy had been becoming stronger in East Pakistan. When Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League won an overwhelming majority in the 1970 Pakistan parliamentary elections, the matter came to a boil. What followed was one of the worst state-sponsored genocides in human history.

For the state of West Bengal, it was a nightmarish action replay of events from almost a quarter century ago. Once again, streams of refugees came in from across the border, in even more wretched condition than before, bringing with them unspeakable tales of horror, anger and discontent. The environment only worsened with the declaration of Emergency in 1975. This is where the reel and real life also merged, bringing to life the angry young man.

One of the worst sufferers of this was the beautiful game in Calcutta. Football matches in Calcutta had always been contested very passionately. But this passion started taking dangerous tones from the early 1970s. The anger flowing through the society started finding its way into the football grounds. The biggest change was in the way footballers were perceived. Even in the 60s, the Maidan loved its footballers. Losses broke hearts but it did not make footballers public enemies. This started changing in the seventies.

Extreme emotions started becoming the norm. In the final of IFA Shield in 1975, East Bengal recorded the biggest ever Derby margin, thrashing Mohun Bagan 5-0. An East Bengal supporter in the ground died, his heart stopping beating from the uncontrolled euphoria. A different tragedy unfolded for a Mohun Bagan supporter. Unable to bear the humiliation, he committed suicide, leaving behind a heart-rending note, saying that he wished to be re-born as a footballer and avenge this ignominy. That night, goalkeeper Bhaskar Ganguly who let in four of the five goals became a hunted figure. Ganguly left Calcutta and stayed hidden in a relative’s place for several days out of fear. Subrata Bhattacharya, one of the greatest players in Mohun Bagan’s history remembers the large crowd outside the Mohun Bagan tent on the evening of that 0-5 match, in frenzied anger. He, along with another player, escaped through the back door and hid in a small eatery on the Strand Road, fearing for their lives. It was 2:30 in the night when the venerable Sailen Manna came, escorted by a police jeep, and rescued the two scared young men.

This became a norm in the mid to late 70s. Victories were accompanied by ceaseless taunting of the opposition. Worse came in losses. Clashes between rival fans became a common affair and often irate supporters took out frustrations on state buses and shops, vandalizing these. The “gora” beating returned in a twisted and ugly form. Quite regularly, when they lost to smaller teams, players from these teams were manhandled. While supporters of all three big clubs indulged in these nefarious deeds, the worst came from East Bengal supporters. Fuelled by anger, their rabid behavior terrorized the Maidan and was portending the oncoming of a tragedy of herculean proportions. Despite their deep affection for East Bengal, Neel Madhab Dutta and Anindit Guha both endorse this quite staunchly.

Although inadvertently, a legend of Indian football may have played some role in the above. PK Banerjee is one of the biggest names of Indian football ever. In the early 70s, after hanging up his boots, he began coaching East Bengal. Prior to him, football coaching in India was more about grooming young players making them technically proficient. Banerjee changed all that. Possessing an astute mind, he quickly realized that a passionate fan base can contribute in a big way to a team’s success. His coaching style played a key role in increasing football frenzy in Calcutta of the 70s. During matches, Banerjee was hugely animated, exhorting his players and bringing the crowd into the mix through his gestures. Everyone loved PK sir – the players, the crowds and the press.

Football in Calcutta was transitioning into the realm of drama. But sadly, the environment of anger and violence in the city meant that this volatile mix could explode any moment. As it did on that fateful August afternoon. Somnath Ata, a lifelong Mohun Bagan loyalist, was a regular at the matches his club was playing. He believes some culpability, albeit indirect, must go to the late Banerjee. His animated behavior, throwing his hands in the air, exasperated facial expressions –contributed to further inciting what was already a volatile crowd, believes Ata.

It is something the iconic Sailen Manna attributed to in his speech at a ceremony to remember the victims of the tragedy. The doyen of Indian football made a plea with folded hands for everyone involved to stop “inciting” players and participants.

Ata’s most telling experiences were recorded a day or two later when he boarded his usual local train. He shared a common passion for the game with several daily passengers who were also regulars like him at the ground. He observed a missing face or two and learnt a few days later that they were among the ill-fated that day.

In any tragedy, some individuals end up grabbing the spotlight – often in an unintended manner. On that afternoon, the man who was thrust into this undesirable position was Dilip Palit. Having been with Mohun Bagan for a while, he had now jumped the fence to sign with their fierce rivals. Such an act was considered an unpardonable sin by supporters of all three major clubs in those days. Surojit Sengupta, a darling of the East Bengal crowd during the glory filled 1970s, had moved to Mohammedan Sporting that year. He was at the ground, covering the match for a Bengali magazine. The fact that he left the ground ten-fifteen minutes before the final whistle – unwilling to take a chance with the venomous wrath of the Red & Gold fans – speaks volumes about the terror that mad football mobs generated in the city then.

Seeing Palit turning out for their arch rivals certainly made the Bagan fans furious. Coach Banerjee, having spent the previous few years with Mohun Bagan knew that Bagan’s pacy left-out Bidesh Bose was likely to cause major problems. He positioned Dilip Palit, known for his physical style of play, in an unorthodox, advanced right wing back position. As play kicked off, Bose was making his marauding runs down the left flank. Repeatedly, Palit was foiling his runs, at times using too much physicality. If a foul was called, the Red & Gold supporters were expressing dissent, fueled on by their coach. If one wasn’t given, their rivals were letting their anger be known in no uncertain terms. The fact that Palit, a Judas in the eyes of Green & Maroon supporters, was involved in the action, was adding to the fire.

Chapter 3

Play audio to immerse into 1980's Calcutta

We spoke with many who were present at Eden Gardens on that fateful afternoon. No matter how near or far they were from the doomed stand, they were affected in some way or the other. Bikash Chaudhuri is an obsessed lover of the East Bengal club. Such was his passion for his club, he went to watch a game a day or two after he was married, antagonizing several family members. On that August afternoon, he was seated far away, almost diametrically opposite the Ranji Stadium. From that far, he could make out something was amiss, but barely realized the extent of the damage.. It was much later, when the dust had settled, that the sight startled him. Prone and lifeless bodies were being lowered from the upper tier to the lower levels, hung down from the edge – some heads up, some heads down. It was a sight that has haunted Chaudhuri for more than 40 years now. While we were speaking to him, we could feel his immense discomfort remembering the scenes, and could only imagine the scale of the trauma that would have consumed him on that day.

The sharp deterioration in the behavior of the football fans in the cities throughout the seventies had an unfortunate casualty – depriving the Maidan of something that may have still played a role in preventing the tragedy on that day. Senior football lovers, who went to the ground to savor the beauty of the game, were increasingly feeling threatened and disappointed with the way the supporter behavior was shaping up. By the late seventies, many of them started turning away from the game they so loved because of the behavior on and off the field. A good example of this was the response that awaited Somnath Ata when he returned home that evening. His father, a football lover himself, sternly ordered him to reduce his Mohun Bagan membership card to ashes. Such was the disgust that had permeated into veteran watchers of the game.

This dwindling number of older, saner heads was a portent to the brewing storm. Moreover, the Ranji Stadium, having the cheapest tickets, attracted a younger audience and consequently, hotter heads. Subhra Kanti Dey was a regular at Eden Gardens then and had watched many matches at the Ranji Stadium. Looking back, he counts himself fortunate to not have picked up a ticket at the doomed stand that day. But even after so long, he finds it incredulous that the authorities had not foreseen a tragedy coming. In Dey’s opinion, the narrow passages and exit corridors were a disaster waiting to happen. It is unfortunate that the ones who were entrusted with the prevention of such an occurrence did not realize the same.

The embers that had been glowing in the stands finally exploded about half way into the match. Bidesh Bose, frustrated at the constant attention from Dilip Palit, lashed out at him. The referee promptly issued Bose a red card. As he exited the pitch, the Mohun Bagan section of the crowd was furious at what they considered biased officiating. But the match official followed this up with something bizarre. Having chosen not to caution Palit earlier, he suddenly flashed out a marching order to him. This was the point that broke the dam.

The respective member galleries housed rival fans thereby preventing them from coming in close contact. The Ranji Stadium, however, housed both sets of fans. People fell on each other like blood thirsty hounds. As unimaginable violence ensued in the stands, quite incredibly the match progressed to a goalless draw. The cops, gloriously unmindful till the final whistle, then proceeded to unleash their batons on the crowd .

As with any incident involving loss of lives in India, the events of 16th August were also followed by the blame game. While the Indian Football Association (IFA) was the agency presiding over the game in West Bengal, the organization of the match was under the aegis of the sports ministry of the West Bengal government. The two exchanged allegations and barbs in the days following the match without any side coming up with a single positive step. It became an extension of the political rivalry between the chief minister Jyoti Basu and opposition leader Priyoranjan Das Munshi who was also the key person calling the shots at IFA.

Amal Dutta, who was in charge of Mohun Bagan for this match wrote this scathing letter to chief minister Basu:

“You have done the right thing by not coming to see the match. In that case, you will have to bear the pain of watching the last breaths of a number of young lives simply due to inaction on the part of your police. … This accident surely disproves your worth whatsoever as ministers for Home and Sports. … You won’t be excused even if you immediately appoint an enquiry commission as mere eyewash. You must have realized the extent of decline of moral values among the youth during the course of Federation Cup football played early in the year. It must be well known to you that football is now more than a game to the Bengali – it is an entity to them. To sustain this entity, large sections of the unemployed, aimless and reckless young society take drugs before and during a match like this. This information is well known to the police department and should have been reported to you by them. Besides this, in the last few years, spectators have got used to cany arms such as blade, razor, knife, brick and iron-rod while watching the matches of their favorite clubs especially in the 60 paise gallery. Whether your police have made any sincere attempt to stop this hooliganism or arrest the culprits is not known. It is really surprising as to how your government could take the responsibility of organizing such an important match without having made any attempts to avert clashes and arrange sitting allotments of rival supporters to two different blocks. In that case, how can you evade responsibility for the disaster?”

In the following days, outrage gripped the city. Newspapers were full of condemnatory letters – many demanding scrapping of football matches altogether. Multitudes were permanently scarred by the horrors of that day. Among them was KK Chatterjee. He had grown up watching stalwarts like Chuni Goswami, Balaram, Ram Bahadur and Thangaraj in the sixties. Professional engagements had kept him away from Calcutta for the better part of the next decade. That day, he had gone to the ground hoping to catch a fascinating contest. What he experienced dampened his enthusiasm forever. He never attended a club game in Calcutta ever again but he did visit the stadium to watch India play in tournaments like the Nehru Cup.

Swapan Kumar Bhowmick, a passionate East Bengal supporter who was present at the ground that day returned home to an anxiety-stricken family. In the coming years, he kept his visits to the football ground a secret.. Singer Manna Dey was an avid football lover and passionate Mohun Bagan fan. He was present at the ground that afternoon. He would later compose and sing a song titled “Khela football khela” that recounted the ghastly tragedy of Eden Gardens. The beautiful game’s popularity was dealt a blow from which many feel it never recovered.

More than forty years later, some questions still remain unanswered and unexplained. Sudhin Chatterjee, the match official, was considered among the best in Calcutta football. Did he simply have a poor day at the office? Or was there something more to it? And, despite knowing how tempers ran wild in a big derby, why were the cops so inert even after the violence erupted? Why were the tell-tale signs of danger at the Ranji Stadium, obvious to spectators, ignored summarily? The IFA claimed that the state government rejected its proposal of separate seating for East Bengal and Mohun Bagan fans. Moreover, IFA’s initiative to have a temporary hospital setup within the Eden premises was also allegedly shot down by the government and police. The former would have perhaps averted the tragedy altogether. The latter would have saved some more lives by ensuring immediate medical attention. Why were these proposals rejected?

On one side of this office, a huge stack of construction rubbish was piled up. A lot of the bricks and stone blocks that were used that day came from this pile. How did this pile escape the attention of the organizers?

A bigger mystery remains in the sudden appearance of huge blocks of stones and concrete chunks in the Ranji Stadium. A week after the match-day, a team of the now-defunct news daily Jugantar went to ‘inspect’ Eden Gardens. The visit led to some shocking discoveries. Just below the Ranji Stadium was a temporary office of the Calcutta Metro Railway which was then under construction. On one side of this office, a huge stack of construction rubbish was piled up. A lot of the bricks and stone blocks that were used that day came from this pile. How did this pile escape the attention of the organizers? There is no satisfactory answer. Even more astounding was the discovery of a partly demolished brick oven, in a corridor on the top tier of D-1 block that witnessed the worst of the action. According to the Jugantar report, these ovens were built to cook meals for the small teams that often come to play at the stadium. Every time before a big football or cricket match, the organizers usually demolished such structures. But when the match began on 16th August, 1980, this oven was still standing intact. During the fracas, bricks were broken off from this oven and used as weapons. Was it simple negligence? For a city long used to witnessing spontaneous crowd trouble, how did not one but two potential sources of “trouble material” escape the attention of the police and match organizers? The answer has remained in the domain of conjecture.

One thing is for certain. Not a lot changed even after this horrific day. While the Calcutta football season was cancelled, pan-India tournaments went ahead as per schedule. In the Rovers Cup in Bombay, these two archrivals clashed again. After a nasty foul, the referee proceeded to give marching orders to an East Bengal player. The player snatched the card from the stunned official’s hand and threw it away and also refused to go off the field. The crowd was riled by this insolent behavior. Among those who were left disgusted at this incident was none other than matinee idol Dilip Kumar. If this incident had taken place in Calcutta, there may well have been a repeat of the 16th August tragedy.

A few years later, in the final of the 1987 All-Airlines Gold Cup, once again the supporters of the two clubs came to blows on the stands. Thankfully, a major untoward incident was averted. As recently as 2009, during an I-league derby at the Yuvabharati Krirangan, Mohun Bagan defender Rahim Nabi was hit on the head by a brick thrown from the gallery. In an eerie replay of that black day, bricks and concrete slabs had almost instantly appeared in the galleries after a controversial red card. Most of the people present that day felt that the bigger tragedy was that no long-standing lessons were learned from the atrocious incident and individuals or agencies whose negligence contributed to this wonton massacre of life went unpunished. The fact that there hasn’t been a repeat is seen as more fortuitous than as a result of preventive measures.

Sixteen lives were lost that afternoon on 16th August, 1980, the youngest being fifteen-and-a-half years old. They had come with dreams of cheering on their favourite team. They returned covered in white shrouds. As decades have passed, the memories of this incident have dimmed in the public mind. But for those who lost their loved ones on that fateful August day, time has failed to heal those wounds.

NOTES

- In his autobiography, Conrad Hunte stated that it was not him but a plainclothes policeman who had retrieved the flags.

- “The Labor minister, Subodh Banerjee, was perfectly clear about what was now generally happening in industrial West Bengal. On 19 June, he told trade unionists in Rourkela that ‘I have allowed a duel between the employees and employers in West Bengal and the police have been taken out of the picture so that the strength of each other may be known.’ There was some indication that the whole apparatus of law enforcement had been pressed to get out of the picture. …” – chapter 10: Road to Revolution, page 324, Calcutta: The City Revealed, Geoffrey Moorhouse

REFERENCES & BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Jugantor newspaper archives 19th – 24th August, 1980

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/174532

- https://www.anandabazar.com/west-bengal/nightmare-and-blooded-history-of-mohunbagan-east-bengal-derby-on-16th-august-1.193730

- https://indianexpress.com/article/sports/football/when-kolkata-derby-turned-deadly-mohun-bagan-east-bengal-tragedy-6556256/

- https://www.sahapedia.org/refugee-colonies-kolkata-history-politics-and-memory

- https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/special-report/story/19800115-india-in-70s-a-turbulent-and-testing-decade-than-any-other-in-the-countrys-history-821750-2014-12-23

- https://www.sahapedia.org/calcutta-1950s-and-1970s-what-made-it-hotbed-rebellions

- https://thebridge.in/featured/nagendra-prasad-the-father-indian-football-removed-prejudice-indian-sports/

- https://indianexpress.com/article/research/fifa-2018-why-bengal-is-obsessed-with-football-there-is-more-nationalism-here-and-less-sport-5217326/

- https://www.indiatimes.com/sports/1967-1996-1999-when-the-eden-gardens-crowd-brought-shame-to-the-city-of-joy-345301.html

- https://english.newsnationtv.com/sports/cricket/did-you-know-doug-walters-targeted-by-communist-party-of-india-vietnam-war-1969-kolkata-test-221149.html

- https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/controversies-in-kolkata-riot-police-fires-and-a-sobbing-vinod-kambli-498547

- https://indianexpress.com/article/research/politics-of-violence-in-west-bengal-when-history-keeps-repeating-itself-5205222/

- https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19851031-indiscipline-in-west-bengal-police-assume-frightening-dimensions-802118-2014-01-14

CREDITS

We are sincerely thankful to all for their time and patience during the research work

Alok Chatterjee, Deepak Majumdar, Subhra Kanti Dey, Anindit Guha, Neel Madhab Dutta, Goutam Ghosh, Somnath Ata, Swapan Kr. Bhowmick, Bikash Chaudhuri, KK Chatterjee, Subhasis Roy, Shiladitya Das, Adisri Guha, Proma Sanyal , Himadri Sekhar Sarkar, Aritra Biswas, Uddalak Das, Suman Bhowmick, Madhurya Chaudhuri, Madhumita Dutta & Surajit Sengupta

We are grateful to

National Library of India, British Library Endangered Archives Programme, Jugantar, Ananda Bazar Patrika and. Amrita Bazar Patrika

Research & Development Team

Research & Development Team

Trinanjan Chakraborty, Abhinav Maitra, Subhajit Sengupta, Aratrika Ganguly, Priyadarshini Basu, Indranath Mukherjee & Srinwantu Dey