The Little Blue House by the Jalongi River

“Ah! There it is,” said our host as he pointed to an odd looking plant a few steps away. I had not seen anything like it before.

As I watched, my mind wandered. How such a seemingly harmless thing could have once been a medium of immense oppression and tyranny?

It was an indigofera tinctoria commonly known as neel (indigo) in these areas.

“The Plants are leguminous in nature so it increases nitrogen levels in the soil thus improving subsequent crop yields, that’s the science behind it” explained our host while still pointing to the indigo plant in front of us. The painful fact however was that between the 18th and 19th century when the natural dye was still the rage and was produced in large quantities across parts of America and South Asia, cultivators were forced to grow it. Indigo has a notorious history of association with slavery and forced labour and there came a time when things rather came to the boil.

In 1858, months after the Company (East India Company) ruthlessly crushed the sepoy mutiny[1], their control over the Indian subcontinent was snatched away and gobbled up by Her Majesty’s ever expanding empire. Company Raj became the British Raj and with it came some administrative changes though the subjugation mostly stayed the same. Another rebellion was just around the corner.

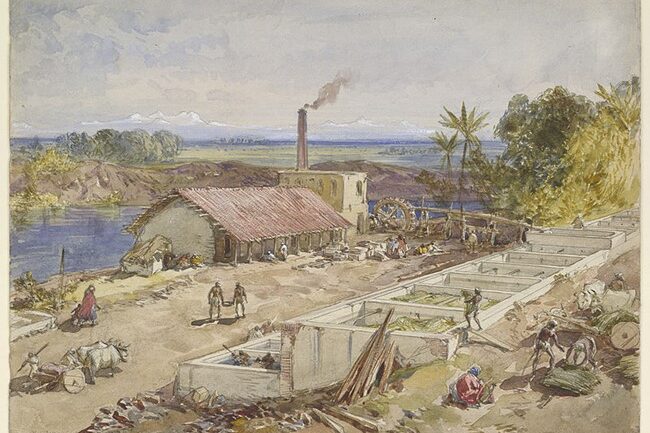

Indigo and opium were the main profit makers for the company, thus, the Empire had no notion of changing it. Areas around undivided Nadia, Murshidabad, parts of Malda, Nabadwip, Kulberia, Jessore (now in Bangladesh) in the undivided Bengal province served as important bases for indigo cultivation.

The ryoti system had prevailed in these areas for a very long time and cultivators were not only forced to grow indigo but were paid very little for it incurring numerous debts along the way. The finished product sold almost at the rate of gold thus christening it as the blue gold.

‘নীলকরের কি অত্যাচার,

এই নীলে সকল নিলে এদের নিলে বোঝা ভার।’

(Oh how torturous are the indigo planters, tis the burden of the indigo among all other things that is the heaviest) – Poem by Ishwar Chandra Gupta on the agonizing effect of indigo cultivation. [3]

After years of deprivation of rights, in 1859, these areas became a hotbed of a peasant uprising. Cultivators not only refused to grow indigo but attacked indigo factories and planters who were mainly European at the time. Villages across rural bengal were up in arms– handmade bows and arrows, slingshots, spears were used as weapons.

The revolt became quite popular though the British government moved swiftly to crush it. A Large contingent of armed police was sent to aid the planters and zamindars. Whoever was found to have even the faintest of connections to the uprising were mercilessly killed and their entire families were wiped out. Peasant leaders like Biswanath Sardar were caught, given a farcical trial and publicly hanged, while many others went into hiding. The revolt and its subsequent suppression left an indomitable mark on Indian and Bengali history, some historians even call it a precursor to the freedom movement that was to come. A year later, as Bengal was still simmering, Dinabandhu Mitra added more fuel to the fire by writing what is still considered to be one of the most important pieces of literature on indigo oppression ‘Nil Darpan’. With its publication ‘Nil Darpan’ instantly caught the attention of both the oppressors and the oppressed and also many native sympathizers among them Harish Chandra Mukherjee, Editor and owner of the newspaper ‘Hindoo Patriot’ and also the Reverend James Long. Mitra, a former student of Long, had sent a copy of the play to the Reverend which left him impressed.

When he mentioned the play to the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal Sir John Peter Grant, Grant told Long to arrange for an English translation of the play. Long eventually did bring out an English translation with his own introduction with the help of Michael Madhusudan Dutt and it made more heads turn than was originally intended. It angered the pro-planters community so much that they dragged the Reverend to court where he was found guilty, sentenced to one month in jail and fined Rs 1,000.

‘My conscience convicts me however of no moral offence or of any offence deserving the language used in the charge to the jury. But I dread the effects of this precedent. This work being a lible, then the exposure of any social evil of caste, of polygamy, of kulin Brahminism, of the opium trade and of many others evils which are supported by the interests of men may be treated as libels too, and thus the great work of moral, social and religious reformation may be checked’ – from the address of the Reverend James Long to the court before passing of the sentence. [4]

As I stood there just outside the house at Moisgunj (actual name – Maheshgunj, corrupted over the years) in the misty cold morning trying to appreciate its charming surroundings it suddenly struck me that words like ‘Neel Bidroho’ felt a little out of place here.

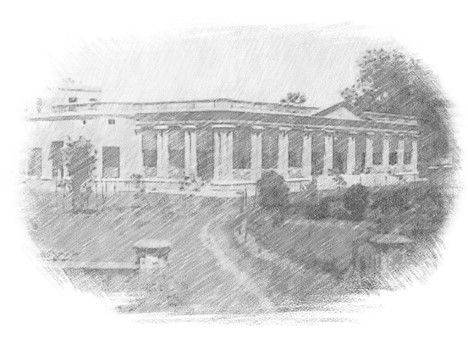

The mansion at the heart of the estate has a dominant French style to it yet its long standing decorated pillars are carefully made to look like a very traditional Bengali zamindar bari. Its teak finished fireplace which has stood since the house was built along with the estate’s beautifully manicured gardens will betray very little of the past where it had served as a neel kuthi.

The Plantation on the banks of the Jalongi River (a branch of Ganges which flows in Nadia) at its peak had almost 200 hectares of land under it cultivating indigo. However, the mansion’s inception is shrouded in mystery. The popular belief as reiterated by Mr Ronodhir Palchoudhury the current owner, is that a Frenchman by the name of John Angelo Savi had built the house sometime in the beginning of the 19th century. Monsieur Savi was an interesting character. Born in Tuscany, trained to be a surgeon, it is said that he had served as doctor to Tipu Sultan, the tiger of Mysore when there were talks of an alliance with the French. His father in law was a certain Marine-General André-François Corderan who had served under the great Napoleon.

The plantation came about as Savi’s need to settle and try their fortune in what was a very booming business at the time.

Indigo plantation was thriving, it was nothing short of a gold rush.

Bengal along with Bihar made up the bulk of indigo production that was exported from British India. However, by the time the second generation of the Savi family came along, the natural dye was starting to fade away.

The Bidroho couldn’t have been very far away from the distinctive red pillars that stand at the main entrance to the estate.

It is said that the word of the rebellion crawled all the way up to her Majesty’s ears. Eventually, after recommendations from its own commission the British government decided to bring laws against forced cultivation.

“Not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood” – E.De-Latour, former magistrate of the Faridpur (now in Bangladesh) while speaking to the neel commission in 1860. [4]

It was around the same time that William Perkin accidentally discovered the synthetic dye while experimenting with aniline and quinine. Some years later, German chemist Adolf von Baeyer would go on to perfect the process and make a fully synthetic replacement of natural indigo dye.

The American Indigo industry also came to a halt in 1865 after the civil war, when laws were made to end slave labour.

It is not clear what really prompted the Savi family to sell the house but with the fortunes of the natural indigo now slowly dwindling, it was probably at that time that they decided to head back to Europe.

What is left as a reminder of that era is that one plant which Mr. Palchoudhury keeps to humour his guests and some cakes of indigo dye which are kept in a closet along with other little treasures, occasionally brought out for curious guests.

The Palchoudhury family bought the place from one of Angelo Savi’s many grandchildren, Henry Nesvitt Savi.

“It was my grandfather,” said Mr. Palchoudhury.

Bipradas Palchoudhury saw an advertisement in the year 1875 while residing in England about the sale of this house and told his brother Nafarchandra Palchoudhuri who was a very prominent landowner at the time to buy it.

Bipradas was born into a very wealthy zamindar family from undivided Nadia. “My grandfather’s relationship with his family was not a very savoury one. When he came back to India after studying in England, he was asked to purify himself or to remain outside. Being a staunch atheist, he chose the latter unsurprisingly. He would buy this house some years later.”

One does get a sense that Mr. Palchoudhury’s grandfather was an attractive man with a certain flavour of seriousness about him by looking at his portrait which hangs on the wall of the dining hall.

“My Grandfather was a very foresighted man and of many talents”, after establishing himself at Moisgunj he would go on to be a pioneer tea planter creating tea plantations all across North Bengal and Assam. “He was a member of the INC, he had built hospitals and banks and helped the community in so many other ways also.”

We were given a souvenir as we were about to leave. Little wooden spoons crafted by Mr. Palchoudhury himself. He did mention that he was very fond of carpentry among other things. I guess having numerous talents runs within the family so to say. He asked if I had seen Thomas Savi’s bed in the other guest room “you should have reminded me to show it to you, it has an arch over it which is very reminiscent of French architecture and is one of a kind”.

Probably next time I said.

Acknowledgement:

We are grateful to the Palchoudhury family for their hospitality and for sharing with us such wonderful insights on the estate’s and their family’s history.

References:

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Indian Mutiny.” Encyclopedia Britannica, November 4, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/Indian-Mutiny .

- “Balakhana – Heritage home stay”. In, 2021, https://www.balakhana.com [accessed 21 February 2021].

- Chanda, P, Nil Bidroho. In, 1st ed., Kolkata, Dey’s Publishing, 2015.

- Das, S, Indigo Cultivation in Undivided Bengal: The History of Indigo Revolt (In Light Of 150 Years). In, Kolkata, Nakshatra, 2014.

- DREW, J, “THE MAN WITH THREE NATIONALITIES”. In The Daily Star, 2018, https://www.thedailystar.net/literature/the-man-three-nationalities-1593940 [accessed 21 February 2021].